Readers,

My apologies for not posting more often. I’ve been busy with my studies (and occasionally reading and writing off-site). There’s been so many new forensics blogs, mailing lists, and infosec communities recently that I’ve been content with reading instead of writing my own posts. Bad habit, I know! I’ve also taken part in a number of security CTF and infosec challenges. I said that I’d be covering past challenges and their solutions in greater depth in my DC3 post and that’s still a plan for the future (if time permits).

I’ve also been toying with the idea of setting up an up-to-date CTF challenge section on site since I have enough content from past CTFs and challenge organizers. We’ll see. I did make a challenge to de-anonymize target onion sites, the solution to which would be in discoverable data about the target web server. But I’ve been told that this might come across as hostile and not helpful for learning purposes, so I’ll probably just end up with standard jeopardy-style questions. Other options include the obligatory stegano in images, sound files, whole forensic images of disks with flags for various forensic artifacts, etc. Since security challenges are time consuming to create, it’ll have to wait a little longer. As always, feel free to subscribe to the blog for future updates.

I’ve also been looking for quality reverse engineering malware resources. I’m still new to that arena but what follows is a list of some really helpful sites, webinars, and books for learning to disassemble programs and study malware both from a static and dynamic perspective. I realize many readers here already do malware analysis, but this is intended for others looking to get into it. Some of the sources are older but all of them are worth checking out. Regretfully I can’t go through every examiner’s quality blog here, but check the site for more links! I’m also happy to read, study, and add any sites or research if submitted.

Malware Resources

Blogs, Articles, Webcasts, & General Papers

Introduction to Malware Analysis by Lenny Zeltser (Webcast), 12/6/2016.

Note – Webcasts, webinars, white papers, blog entries, conferences, I’ve seen a lot of Lenny Zeltser’s work and I’m a big follower. So I often link to his work.

Malware Analysis: An Introduction (GIAC Gold Paper) by Distler. 12/14/2007.

5 Steps to Building a Malware Analysis Toolkit Using Free Tools by Lenny Zeltser. 3/14/2015.

Malware Analysis Essentials Using REMnux w/ Lenny Zeltser (Webcast), SANS Institute, 4/17/2014.

4 Cheet Sheets for Malware Analysis by Lenny Zeltser, SANS Blog, 9/13/2017.

Analyzing Malicious Documents Cheat Sheet by Lenny Zeltser. 9/7/2017.

Thoughts on Malware, Digital Forensics, and Data Breaches by Hal Pomeranz, SANS Blog, 1/18/2012.

CyberBit’s 5 Open Source Malware Tools You Should Have in Your Arsenal

Projects To Watch/Tools to Know:

FLARE VM – The Windows malware platform by FireEye, a company known for their malware analysis and incident response know-how. 1/16/2018 Update: This tool is really outstanding. The packages can be imported into any VM, preferably newly rolled evaluation copies of Windows 10 VM, since you can just keep restoring back if you max the 90 day eval. Flare includes many tools for file analysis out-of-the-box such as hex editors, debuggers, disassemblers, text editors, PE tools, process hacks, packet analyzers, alternate data stream manipulation tools, and more (official list on Github). Package installation is made simple with Chocolatey. My own custom box includes essentials I downloaded such as OWASP ZSC for Python shellcode generation, Yara, stegano detection tools, audio editors, and more. Definitely not an exaggeration to say that you can make this into the best security platform available on Windows.

REMnux – A Linux Toolkit for Reverse-Engineering and Analyzing Malware

Kali Linux – I use Kali a lot so I highly recommend it. It’s an extremely well maintained distro, adding your own packages as needed is simple and usually everything just works (thanks to all the modules and dependencies pre-rolled into Kali). There are some great tutorials for pentesting and forensics on Udemy and through Offensive Security. Adding malware tools is easy.

SIFT Workstation – I’ve used multiple versions of SIFT from Linux to Windows 7 and 10. I highly recommend it for forensics work. It does have more timeline tools than Kali (although you can add packages to Kali as you see fit). SIFT VM + Kali VM = ideal. I have heard great things about BlackArch for penetration testing but have yet to try it (I do have fond memories of Archlinux and Archbang, so it’s on my to-do list).

Yara Analysis Tool – industry leading tool in signature and behavioral rule-set matching for malware.

Cuckoo Sandbox – Sandboxing tool for malware. If you’re just using VMware, be careful of VM escape vulnerabilities, bogging down resources, etc.

IDA & IDA Pro – Ideal for static analysis. Disassembler for every major operating system. I’ll be honest, my assembly skills are weak, but this is one tool worth sticking with. There’s even a great No Starch book on IDA to help you out! (IDA Pro Book, 2nd Edition by Chris Eagle — fair warning, the assembly sections are pretty light and assume you know what you’re doing, so I’d suggest supplementing it with another resource to familiarize yourself with the subject prior to diving into IDA. One good (and free) course is the x86 class by Open Security.)

OllyDbg – The Gray Hat Hacking books use OllyDbg a lot.

Automatic Malware Analysis and Sandbox Services by Lenny Zeltser

Classes:

Introductory Intel x86: Architecture, Assembly, Applications, & Alliteration w/ Xeno Kovah (Open Security Training)

Introduction To Reverse Engineering Software by Matt Briggs & Frank Poz (Open Security Training)

Reverse Engineering Malware by Matt Brigs & Frank Poz (Open Security Training)

FOR610: Reverse-Engineering Malware: Malware Analysis Tools and Techniques with Jake Williams (SANS Institute)

Note- I haven’t had a chance to take this class but it’s pretty much the de-facto malware analysis class in digital forensics.

Again, there are many courses and tutorials available through Lynda, Udemy, and YouTube. Here… hold up. There we go (had to do it!).

Technical References:

Tech refs can be expensive but these are totally worth it if you’re committed to learning the subject matter (or, like me, you’re equally committed to making a visually impressive security bookshelf /modestyfail). Most well-maintained, high traffic libraries should have some of them. Sure, there are plenty of online sources with similar information but these texts are definitely helpful.

Malware Analyst’s Cookbook: Tools and Techniques for Fighting Malicious Code by Hartstein, Richard, Ligh, and Adair. 2010.

Note: It’s the bible of malware analysis. It was one of the first larger-works to tackle malware head-on. While it isn’t as technically in-depth for complicated tasks (I found that GHH was more technical for some things), it’s a must have. New to malware analysis, I can honestly say it’s readable and worth checking out.

Black Hat Python: Python Programming for Hackers and Pentesters by Justin Seitz. 2015.

Note: One of my all time favorites. Black Hat-style techniques are explored using Python code and popular modules. There’s something for everyone here. (I often use BHP or GHH – mentioned below – as a springboard for Python projects, so I can also recommend getting physical copies as opposed to eBook versions.)

Gray Hat Hacking, 2nd Edition & 3rd Edition by Harper, Harris, Ness, Eagle, Lenkey, Williams. 2008 & 2011 respectively.

Note: When I first picked up the 2nd edition from the library I had no idea what IDA Pro was and wanted more on pentesting. Immediately dismissing GHH something I wouldn’t use. In retrospect, GHH is an awesome guide to DLLs, handles, processes, reverse engineering, and malware analysis.

Data Hiding Techniques in Windows OS: A Practical Approach to Investigation and Defense by Hassan & Hijazi. 2017.

Note: This book should just be called “How to Win at CTF Every Time.” While it doesn’t explore malware in-depth, it does talk about various forms of data hiding and data manipulation (ADSs, stegano, etc). Since malware utilizes different methods of remaining hidden, DHTIWO is a great guide for developing critical thinking skills. This and File System Forensic Analysis by Brian Carrier are so easy to use as regular resources in forensics.

Violent Python: A Cookbook for Hackers, Forensic Analysts, Penetration Testers & Security Engineers. TJ. O’Connor. 2013.

Note: I used to really love this book prior to finding BHP and the Gray Hat books. It has drone hacking and Twitter OSINT hacks, what’s not to love? The code is hit or miss but it has some good ideas for Python coders. It does also contain a section on Virus detection. I prefer Justin Seitz’s work, but respectful nod to TJO’s great resource.

Miscellaneous Resources:

Mitre’s CVE Page (Security Bug/Exploit Lookup)

Yara Official Documentation

Yara Definitions & Rulesets

Offensive Security’s Exploit-DB (Exploit Lookup & Sample Code)

Also check the links to other blogs around the site as there are a fair amount that cover malware research.

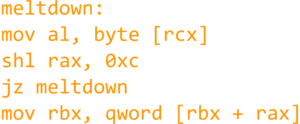

Meltdown & Spectre Links

Meltdown Paper | Spectre Paper | FAQs: https://meltdownattack.com/#faq-fix

You know that feeling when you’re lurking darknet forums or Inj3ct0r for information on new malware and you’re like, “what a liar, that’s not a revolutionary 0day exploit, that’s yet another buffer overflow exploit!” This is a fair bit more serious.

Thanks to Jann Horn and the analysts at Google Project Zero, two new dangerous exploits were discovered. Spectre – which leverages a processor’s speculative execution to pull data from memory to an attacker via side channels* – and Meltdown – which uses out-of-order code execution on processors to leak sensitive information across any form of virtualized environment or through any form of protected memory space. Unfortunately, fears are that they’re so deeply embedded in modern processor architecture that they’re nearly impossible to temporarily patch without crippling current infrastructure. They aren’t entirely software issues that can be patched easily. Dynamic execution speeds up computing performance drastically while Spectre potentially effects so many different types of processors. I’ve tried to include some useful links here for understanding the severity of Meltdown and Spectre.

* Yes, Spectre sounds like the coolest thing since poptarts. So much for professionalism.

FireEye Notice for CVE-2017-5754, CVE-2017-5753, and CVE-2017-5715 (FireEye), 1/5/2018.

Researchers Discover Two Major Flaws in the World’s Computers by Cade Metz and Nicole Perlroth (New York Times), 1/3/2018.

The Complete List Of CPUs Affected By Meltdown / Spectre by Dr. Adrian Wong, 1/8/2018.

In response to worries of Spectre being able to extract passwords from application password managers and vaults, Dashlane’s Eitan Katz wrote an article on the state of Dashlane and what Meltdown and Spectre do. Check it out here: Meltdown and Spectre: What you Need to Know to Stay Safe by Eitan Katz (Dashlane), 1/5/2018.

It’s not every day you see patches that cause entire Linux communities to freak out. If you’re an Ubuntu user, be sure to check out this article regarding Ubuntu 16.04’s patch: Meltdown & Spectre Patches Causing Boot Issues for Ubuntu 16.04 Computers by Catalin Cimpanu, 1/10/2018. The patch in question only applied to Meltdown. The problem was fixed with subsequent updates after the article was released.

Be sure to check out the CVEs below for more technical information about each of the exploits. The links contain a lot of critical information such as sample source code that you can attempt to run in a virtual environment. Note that your mileage may vary in VMs, some have reported BSoDs and not useful crashes when attempting to execute the exploits.

Spectre CVEs: https://cve.mitre.org/cgi-bin/cvename.cgi?name=CVE-2017-5753 & https://cve.mitre.org/cgi-bin/cvename.cgi?name=CVE-2017-5715

Meltdown CVE: https://cve.mitre.org/cgi-bin/cvename.cgi?name=CVE-2017-5754